Is it the time of year? Or has the air changed in politics? In the mayhem of Truss’s economic catastrophe, are we witnessing the green shoots of Britain’s psychological recovery?

The way the air changes in September. Summer clings on, sometimes, but then there’s that familiar nip, and things suddenly feel different.

It’s not the first time the Tory governments of recent years have taken bizarre decisions against the interests of the British people, but it is the first time they have been so swiftly and so decisively called out.

A YouGov poll on Monday showed that, across all age groups, pretty much nobody had confidence in Truss’s government’s ability to tackle the rising cost of living.

No doubt, the immediacy of the market response – the ‘flash crash’ of the pound – has helped the public to see the rashness of Kwarteng and Truss’s mini-budget for what it is.

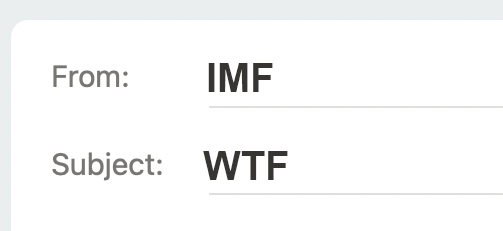

Now even the IMF has issued its statement of dismay, summarised nicely here by the Have I Got News For You social media team:

via HIGNFY

Perhaps the cabinet can be forgiven for thinking they would get away with it. After all, they got away with austerity, they got away with Brexit, and during peak Covid they got away with the siphoning off of public funds to friends, family and donors.

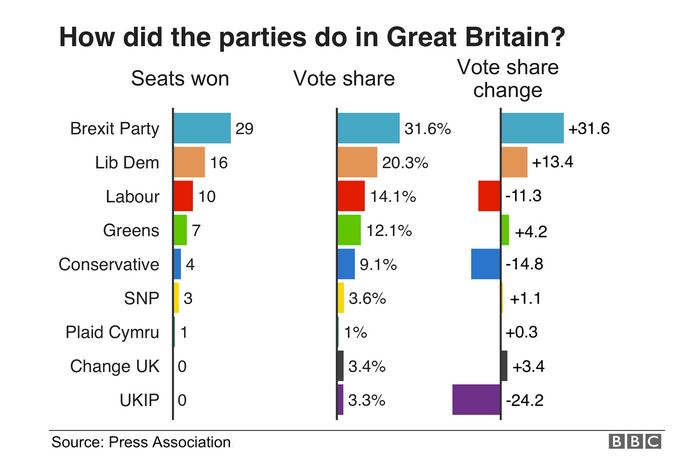

But the effects of Brexit were harder to see, masked by transition periods, covid, disinformation, and the blinding nature of faith. Brexit benefited also from a democratic mandate of sorts. Flawed, corrupt, and based on a mountain of shameless lies, but nevertheless there.

The present stance of Truss and Kwarteng, on the other hand, has precisely no mandate. Pouring scorn on redistribution, they have promised public money in unprecedented, economy-crashing sums to ‘big oil’ and gas, and tax cuts for the very rich – entirely disregarding their party’s repeated commitments to ‘level up’. It’s the opposite of a mandate.

No wonder the public is unimpressed. There’s no hiding this one behind ‘will of the people’. It is will of the hedge funders. It’s will of Tufton Street. It’s will of the arch libertarians and the disaster capitalists.

Speaking of Tufton Street, that’s something else that’s changed. The BBC has finally published an article, and radio programme, on ‘the other black door shaping British politics’.

Tufton Street’s shady influence won’t be news to those familiar with the weeds of politics, but it might be news to the general public. Until now it seemed they didn’t want to know. But now, with such a bizarre departure from any semblance of fiscal caution, such a shameless favouring of the already wealthy, the public is inevitably going to ask what’s behind it. Where there is a bad smell, you look for the source.

Some of that bad smell emanates from the prodigious profits of hedgefunders who have bet against the pound and UK gilts, making big money out of our national misfortune.

(They did this before, of course, making substantial donations to the Brexit cause, only to reap gigantic rewards in the sterling slide which inevitably followed. But Brexit was different. That mandate again.)

The bad smell is particularly strong around the links between these hedge funders and our chief policymakers. They seem to have worked for each other, funded each others’ startups, and met up at what would appear to have been opportune moments.

Even if there has been (as is claimed) ‘no trading benefit from these relationships,’ the seemingly-close alignment of people, policy, prediction and profit is going to be hard to stomach for a public fretting about heating and eating, inflation and borrowing costs.

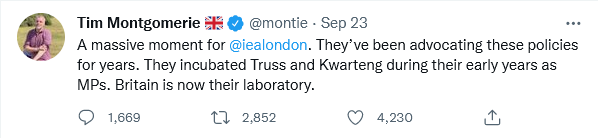

But locating the source of the smell is not just about who profits. It’s about why. What possible line of thought brings us here? Tufton Street provides much of the answer. We learn that its opaquely-funded outfits have been nurturing the likes of Truss since forever, inculcating in them their vision of the UK as a billionaire sociopath’s nirvana: small state, deregulated, safety-net free. We learn that now, with the successful installation of Truss in No 10, the UK has finally become their ‘laboratory’.

Yes, we are lab rats in a mad experiment. And they are saying it out loud.

Maybe that’s why the air seems to have changed at the BBC, too. Maybe that’s why it has chosen now to begin to shine a light on Tufton Street. It might not be the very first time it has done so, but it certainly feels like it. It feels like the BBC is daring to break free of its internally- and externally-imposed constraints.

BBC news’ reporting seems more direct in the last day or two, describing the economic fallout of Truss’s plans with cold, incisive clarity, for example, and reminding viewers, right up in the headlines, that a falling pound, by making imports more expensive, only worsens inflation, while requiring interest rate hikes – which further exacerbate the cost of living.

Watching and listening to their coverage, it really feels as if they’ve decided they’re not frightened any more. It really feels as if the BBC knows the Tories’ number is up, and there is no longer any benefit in kowtowing.

Meanwhile, in Liverpool, Labour seem to have had a remarkably upbeat conference. Delegates’ excitement was palpable. The intention to renationalise the railways, the bold green policy, the insistence on sound money. And above all, the confidence to paint a picture of a rosier future. I was struck by the lady who, interviewed after the leader’s speech, said that Starmer had restored her hope, after her husband died following a traumatic six-hour plus wait for an ambulance. She wanted someone to turn the NHS around, and Starmer convinced her that he would. Change was coming.

Perhaps most comforting of all are the little anecdotes you pick up here and there. A couple of ladies in the hairdresser in affluent Esher, card-carrying Tories, overheard declaring that the tax cuts for the rich were ‘just not fair’. Or the die-hard Brexiteer in a family WhatsApp group finally saying he’s made up his mind to vote Labour – ‘Starmer’s got his act together, and the Tories have lost the bloody plot’. It might be September, but are these the green shoots of Britain’s psychological recovery?

None of this is to forget the power of the Tory campaigning machine. They won’t go down without a fight, and they fight below the belt. Anyone who is sure we’re on the brink of a ‘97 moment, and not a 1992 stumble, is naive.

But the British public, like its supine public broadcaster, seems to be waking up. For twelve years, the Tory emperors have worn no clothes. Suddenly, their dishonesty, their folly, their callous, naked greed, is there for all to see.

Updated 28 Sept 2022, 15:40 with minor tweaks and additional images.

Updated 29 Sept 2022, 14:47 to reflect Labour conference has finished.