16th May, 2010

A big and slightly scary man came and sat next to me at Wembley yesterday. Nodded hello. Sat quietly for a bit. Then suddenly stood up, spread his arms and screamed “I DIE!”

It took me a moment to realise he was joining in with the song, arriving without warning at our section of the ground, which goes “Portsmouth till I die, Portsmouth till I die, I know I am, I’m sure I am, I’m Portsmouth till I die.”

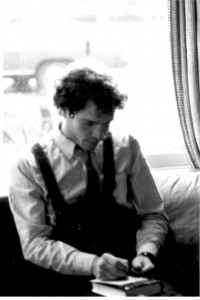

In the post on the morning of the Cup Final, I found a clipping kindly sent to me by a fellow Pompey fan. It was an article from 2003 by Anthony Minghella writing in The Times, about the joys and miseries (mostly miseries) of following Portsmouth, and his then obsession with the computer game Championship Manager. Even in the fantasy version, the problem was that the cast-offs off one of the rich clubs would cost more than (and beat) a Pompey 1st XI.

The economics of the game, aside from being unsustainable – I guess you didn’t need to be brain of Britain to see that coming, even in 2003 – were spoiling the fun of the game by preventing a level playing field.

So yesterday, we were playing a Chelsea XI picked from a squad worth around £300m. Ours, to be sold in an emergency fire sale, I guess starting tomorrow morning, might yield £35m.

Looked at that way, our 1-0 defeat was nothing less than a miraculous victory.

I felt a little blue on the way home. You always hope, especially in the FA Cup, that you can pull off a cheeky win. That’s the romance of the Cup. But actually what I noticed was that I was feeling better than I felt on the return journey after our FA Cup victory in 2008.

I thought at the time that it felt hollow because Anthony should have been there to share it with us. His last message in my inbox says, “I hope there’ll be a few games for me soon”. We had never experienced anything like an FA Cup Final for Portsmouth, and life is indeed cruel that it did not afford him that opportunity.

Another reason for the muted joy was that we did not convincingly thrash Cardiff City. The game seemed slow and unexciting, perhaps a function of the size of the stadium and the distance from the action. We Pompey fans are used to the bearpit that is Fratton Park.

But I don’t know. Was it really the absence of Ant? Or the less-than-thrilling football? Or was it the fact that Pompey won the FA Cup, when we never win anything?

I suspect it was the latter. Anyone who by accident of birth finds themselves singing the Pompey chimes will know that the tune, and the loyalty, stays with you. Pompey fans do not grow up and become Chelsea fans or Man U or Liverpool. Pompey fans are Pompey till they die.

That’s all well and dandy, but Pompey never win. Sure we have the occasional run, but basically we’re crap. The lot of the Pompey fan is to arrive full of hope, sing his heart out, terrify the visiting team with the best and most vocal support in the land – and then to depart crestfallen.

My experience of following Pompey is mostly about the long, dejected journey home. After years of that sensation, it comes to be the desired outcome. Pompey fans have a perverse but Pavlovian response to loss, which is to pick themselves up and come back for more. I noticed two banners among the crowd: one, optimistically, called for “Pompey in Europe”. The other, a more accurate reflection of the Pompey character, declared, “You will never break our spirit.”

So, travelling home after the match, contemplating my own private woes, and the very public woes of Pompey – Cup defeat; relegation; unimaginable debt; the forthcoming firesale of the squad; a bleak, impossible future – I found myself oddly comforted by the familiarity of it all. We are losers. We are stoics. We are loyal. We are Pompey till we die.

If there has been a quintessentially ‘Pompey’ moment in PFC’s recent history, this was it. And so, more than after the 2008 victory, I wished Ant had been there with me, analysing, bemoaning, sharing and – finally – savouring defeat.