21.4.2012

I’m emotional, suggestible, and – if not exactly superstitious – a romantic believer in signs and auguries.

So, today, as possibly the last ever professional game of football takes place at Fratton Park in Portsmouth, I celebrate this remarkable coincidence.

Growing up in Ryde, Isle of Wight, there was only one football club I could support: Portsmouth. My father lived in Portsmouth in the 1930s as a boy, and remembers the huge crowds, the FA Cup pride, and still follows Pompey to this day, at 90 years of age. My brother Anthony inherited this affection for the club, as, inevitably, did I.

We used to take “the football boat” from Ryde, and when Anthony’s fortunes improved, he would buy us ‘posh’ tickets in the middle of the South Stand. (Anybody who has been to Fortress Fratton will know that the word ‘posh’ can only be applied in the loosest sense, but that is very much part of its charm.) When Anthony died, my sister and I toyed with the idea of keeping his season ticket going, leaving his seat symbolically empty. Pompey is part of our story: our history, and, hopefully, our future. We’ll see.

We used to take “the football boat” from Ryde, and when Anthony’s fortunes improved, he would buy us ‘posh’ tickets in the middle of the South Stand. (Anybody who has been to Fortress Fratton will know that the word ‘posh’ can only be applied in the loosest sense, but that is very much part of its charm.) When Anthony died, my sister and I toyed with the idea of keeping his season ticket going, leaving his seat symbolically empty. Pompey is part of our story: our history, and, hopefully, our future. We’ll see.

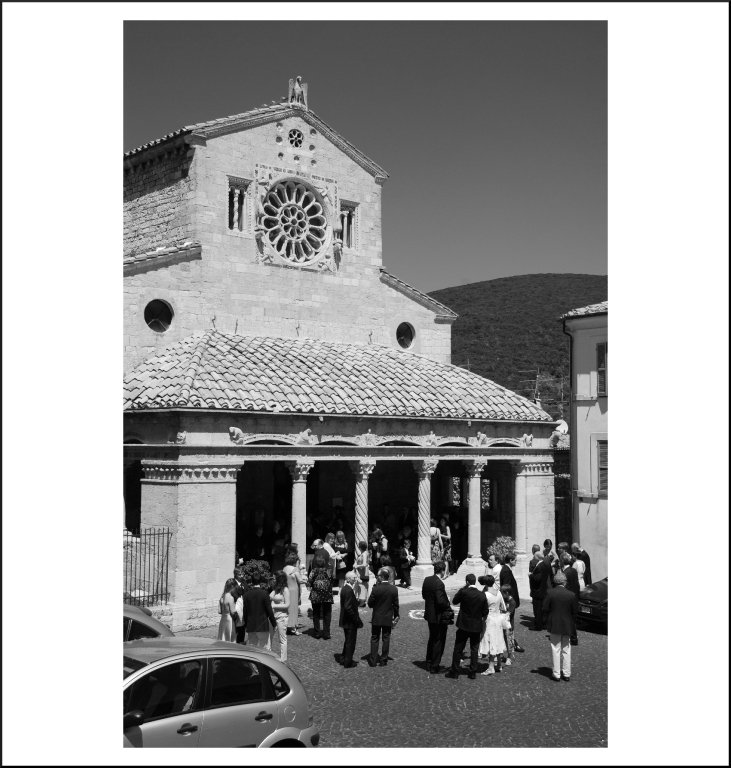

In recent times, I have taken to spending a part of my year in Umbria, Italy, just north of Rome. There is no family connection there, just a love of the place. I have found an increasing sense of belonging in a wonderful hilltop town on our doorstep called Lugnano in Teverina. When I recently went to report a burglary to the police there, the carabiniere made me describe everything to him in painstaking detail, enjoying my comic struggle with Italian, before revealing that he knew everything already: word gets round in a town that small. You either love that kind of thing or you hate it, and I love it. It’s a totally brilliant community.

In recent times, I have taken to spending a part of my year in Umbria, Italy, just north of Rome. There is no family connection there, just a love of the place. I have found an increasing sense of belonging in a wonderful hilltop town on our doorstep called Lugnano in Teverina. When I recently went to report a burglary to the police there, the carabiniere made me describe everything to him in painstaking detail, enjoying my comic struggle with Italian, before revealing that he knew everything already: word gets round in a town that small. You either love that kind of thing or you hate it, and I love it. It’s a totally brilliant community.

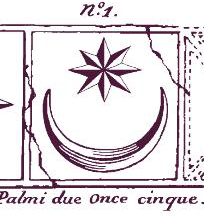

Finally, I adore red wine. I know next to nothing about white. But a wine dealer friend, the excellent Sebastian Peake, forced a case of a particular white on me a few years back. It’s a vermentino and it is a revelation, a small shipment from heaven. I associate it with a physical release of tension – that tightness in the pit of the stomach that tough days can induce dissolves with the first glug of this particular cool, minerally (but smooth) wine. Actually ‘dissolves’ isn’t the word. The tension snaps away before the wine even hits the back of the throat, in what can only be a pavlovian response to its aroma.

Finally, I adore red wine. I know next to nothing about white. But a wine dealer friend, the excellent Sebastian Peake, forced a case of a particular white on me a few years back. It’s a vermentino and it is a revelation, a small shipment from heaven. I associate it with a physical release of tension – that tightness in the pit of the stomach that tough days can induce dissolves with the first glug of this particular cool, minerally (but smooth) wine. Actually ‘dissolves’ isn’t the word. The tension snaps away before the wine even hits the back of the throat, in what can only be a pavlovian response to its aroma.

These are small things, I know, but the heart is somehow enriched by them. The community of club, of shared memory, or of a few hundred people in a hilltop in Italy who know your business. The way a flavour can become a friend. In the end these small things come to define us. Our habits and our homes. The places where we will be missed. The tables at which we no longer sit. The choice of wine no longer exercised.

I don’t know. I like small things. If, as Hume suggested we are just bundles of memories, then perhaps the small things, those tiny snippets of moments we can smell, are the most important elements of selfhood. The briny post-nasal hit of Portsmouth Harbour, up the ramp to the platforms and herding onto the Fratton train. The warm embrace of community. The bliss of wine unwinding. Elusive things. Intangibles. Spaces where we once were. Whiffs of us.

I mentioned a startling coincidence, and here it is. I won’t make too much of it. I won’t indulge my romantic side. But it feels appropriate today, when the future of Portsmouth Football Club hangs in the balance, and tens of thousands of hearts on the south coast may forever be broken, to share it with you: a common thread between some of my favourite things. It’s as if the gods meant it all to be. Play up Pompey.

The logo of Portsmouth Football Club.

The coat of arms of Lugnano in Teverina.

The wine label.