“The boss”, as his sycophant colleagues insist on calling him, is back. Like a caped crusader, recovered from a brush with kryptonite. Physically weakened, perhaps, but with new, heroic resolve to take on the enemy. Vim, my friends, and vigour. Grit and guts.

“The boss”, as his sycophant colleagues insist on calling him, is back. Like a caped crusader, recovered from a brush with kryptonite. Physically weakened, perhaps, but with new, heroic resolve to take on the enemy. Vim, my friends, and vigour. Grit and guts.

But many found Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Downing Street back-to-work address nauseating. Not least because he made almost no mention of the astonishing suffering and loss of life, or the cloud of grief descending upon our land, talking instead of the UK’s “apparent success” in combating the “invisible mugger” that is Coronavirus.

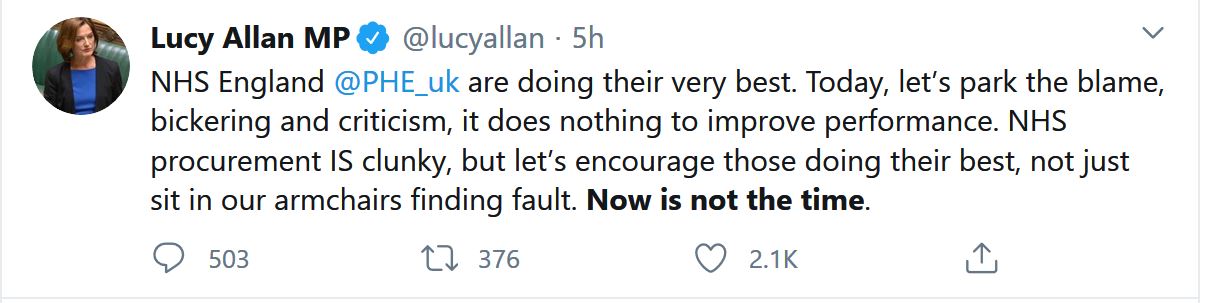

How does a man who has presided over the calamity of our lifetimes dare to stand in front of us and talk of “success”? A man whose inaction and hubris in January and February – not to mention those fateful, shameful eleven days in March – was tantamount to welcoming the Covid-19 “mugger” into the UK with open arms and a free (blue) passport. With the country on course to have one of the worst per capita death tolls in the world; with 45,000 or so lives already lost; with families grieving up and down the land and unable even to attend funerals; with 5,000 new cases a week, what on earth was he thinking?

The answer is there in plain sight – in his relentless insistence on “protecting the NHS”. (Rich, I know, coming from the Tories who have choked the NHS for a decade, frozen nurses’ pay, demonized its European staff, and who even now fail it on a daily basis with their incapacity to deliver basic equipment – and yet they have the temerity to clap on Thursdays and call it “our NHS” … But bear with me. The sheer unlikelihood of the Tories suddenly falling in love with state provision is the clue to understanding Johnson’s evident satisfaction with the current state of affairs.)

Remember Johnson’s “powered by love” speech after coming out of hospital, on 12th April? He waxed lyrical about the NHS, his nurses Jenny and Luis, and about the spirit of the British people, whose lockdown struggle was elevated – by sheer power of grandiose rhetoric – from fretting at home to a heroic defence of the nation and its health service, conjuring up images of brave Brits linking arms around the perimeters of our hospitals, ready to repel for Queen and country.

“We are making progress in this national battle because the British public formed a human shield around this country’s greatest national asset: our National Health Service.” (12 April 2020)

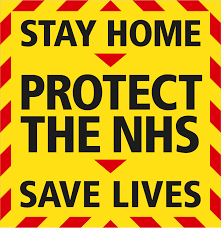

This idea of the public as some sort of people’s army championing the NHS, though vividly painted here, wasn’t new. It’s been there in our daily diet for some time now. We’ve been exhorted not, as might have been expected, simply to stay at home and (thereby) save lives, but to stay at home, protect the NHS and save lives.

What work is this extra clause doing? It doesn’t change the overall instruction. It doesn’t give us anything more to do or not do. Our lockdown cabin fever stays the same. As instructions go, “Protect the NHS” is a weird one. Its insertion feels like a “tell”. And the way it sits awkwardly in the middle like that, it sometimes feels like the ‘protecting the NHS’ part is more important than the ‘saving lives’ part. Sometimes the graphics reflect that feeling, too.

Of course, the notion of us protecting the NHS is the wrong way round. Notwithstanding our duty – shamefully neglected – to protect its staff, the NHS is there to protect us. That’s its purpose. Our “greatest national asset” is not the NHS, it is us, the people. The clue is in the name: it’s a service. Our service. To protect us and care for us. But Johnson congratulates us for forming a human shield around it, as if our job were to sacrifice our lives for it, rather than turning to it for salvation in our gritless, gutless hour of need.

Of course, the NHS can only protect us if we don’t overwhelm it. There’s no doubt that we have all had to play our part in flattening the curve, otherwise the NHS wouldn’t have been able to cope. Flattening the curve has meant we’ve delivered patients at a steadier pace, and nurses like Johnson’s Jenny and Luis have, just, been able to manage. Fewer people will have died than would have been the case if the patients had all presented in one big wave. We get that. We know why we’ve stayed at home.

But our core interest is in saving lives. For us, the NHS is a means to that end, not an end in itself. In contrast, Johnson’s language reveals, time and again, that his priority is to be able to say that the NHS has coped, no matter how many people have died. Saving lives is secondary. Saving lives is in smaller print. When he describes the NHS as “the beating heart of this country”, it’s as if he has substituted the NHS for the people; as if he has forgotten the actual beating hearts of the country. And indeed the ones which have stopped beating.

“We will win because our NHS is the beating heart of this country… It is unconquerable.” (12 April 2020)

This warped love for the NHS makes sense if his greatest fear has not, in fact, been a death toll the size of the entire WWII Blitz. It makes sense if, on the contrary, his greatest fear has been the dire imagery of an NHS in collapse. Large numbers of patients dying unattended in corridors, or in ambulances queueing outside. Medics despairing. Emergency services unable to respond. All manner of collateral chaos. The inevitable media reports would be beyond his control, and his premiership would likely be over. The images would endure for generations.

That collapse has, somehow, and mercifully, been avoided. The unfolding care home disaster, which has involved the exporting of demise to disparate locations, far from the hospital front lines, may be part of the explanation. And shattered, lethally under-equipped NHS staff might say that calamity has been far closer than the public realises.

Certainly the families of those staff who have lost their lives will find little comfort in the idea of the NHS having been spared complete collapse. Their worlds have been destroyed. The same goes for the families of all of the 45,000+ victims. There is no consolation for them.

But for Johnson, the difference between near-breakdown and total breakdown is all the difference in the world. The optics of a visibly collapsed NHS would likely have been terminal. An ocean of kryptonite from which, this time, there could be no heroic return. The unconquerable would have been conquered. But the invisible deaths of coronavirus, in which loved ones disappear into an ambulance never to be seen again, seem not, yet, to be damaging him.

Small wonder, then, that in his back-to-work address, he saw no problem in stepping over the invisible dead, and talking instead about our “progress” and our “apparent success”. Because, from where he’s standing, a vital mission has indeed been accomplished. The mission, at all costs, to prevent the NHS from appearing to be in meltdown. The mission to save face. The mission, ultimately, to save Boris.

“We defied so many predictions. We did not run out of ventilators or ICU beds. We did not allow our NHS to collapse.” (27 April 2020)

Johnson and his sycophants have not suddenly fallen in love with the notion of state health care. They don’t profess to love the NHS because it saves you and me. They love it because – for as long as it appears, however narrowly, to be coping – the NHS saves them.

“… if we could stop our NHS from being overwhelmed, then we could not be beaten… ” (12 April 2020)

Our “human shield” around the NHS is really a shield around the incompetence and arrogance of a Prime Minister who was repeatedly warned there was a “mugger” on the path ahead, but blithely took us that way anyway.

Since then, he has sought to mug us, by hijacking our appreciation for the NHS and twisting it with weasel word-play into a truly remarkable political bomb-shelter. So far, he must be thinking, “apparent success.”

Thank you for reading. Please help me reach more like-minded people, using the sharing buttons below.