And here’s Louisa’s brilliant, punky take on Big Yellow Taxi.

A 99 with that?

Today is my Dad Edward’s 99th birthday.

In the old days on the ice cream vans, he would cheekily ask his customers whether they wanted a 99 with that, or just a flake. Both answers meant a flake, and this man’s mischievous patter sold a lot of flakes.

Here he is winning (and, quite frankly, cheating) at cards, last year.

I’ll tell a tiny story about him for his birthday.

Many people know about his achievements in public life and business on the Isle of Wight. He is much loved there, and the only Freeman of his town, Ryde.

Not so many know that both he and our Mum grew up without fathers. Edward’s dad, Antonio, died with an unknown fever in 1927, when Edward was only five years old.

So there was no role model, in our family, for how a father should be.

You’d think that would be a recipe for royally screwing up. But Dad was gentle and loving, a true family man, with great belief in, and ambition for, his kids. If I were half as good a father as he has been, my own kids would be lucky. Now and then he takes me to one side and advises me to be kinder, to take a breath when irritated, to see the big picture, and understand the smallness of the child. He’s always right.

Anyway, once when I was at university, we had a couple of games of Scrabble at home before I set off for a new term. He trounced me, and thought it was hilarious that he could beat me, an Oxford student, in a language which he had not learned as a child (after Glasgow, he was in Paris and then Italy until young adulthood). Furthermore, he had had only three years of school in his entire life, and those before the war in rural Italy. Waving me off, he gave me a card.

Unpacking at Oxford, my friend from a tough northern background came round to say hello. He spotted the card on my mantelpiece. Inside, my Dad had written “Sorry for beating you” and slipped in a fiver, which I had not yet pocketed. My friend was really worried. He looked at me with pity and concern, and asked me if I wanted to talk about it. “What?” I said, still unpacking. “Your Dad,” he said. “Your Dad beating you.”

My friend’s Dad, it turned out, had a temper. A violent temper. My friend was sorry that I too was suffering in this way – and being bought off with a lousy fiver, to boot.

Nothing, of course, could be further from the truth. Machismo and aggression – much more common in those days of course – did not exist in our lives. Our Dad’s self-taught mode of fatherhood was all about gentleness, togetherness, and belief. It wasn’t perfect, of course, but the core of it was the open-armed safety of family, and massive, massive heart.

That little moment at Merton College, Oxford in 1988 made me realise that there are many kinds of fathers, and I was blessed with a great one.

Here, as a bonus flake in your ice cream (or a 99), is a mini life in pictures:

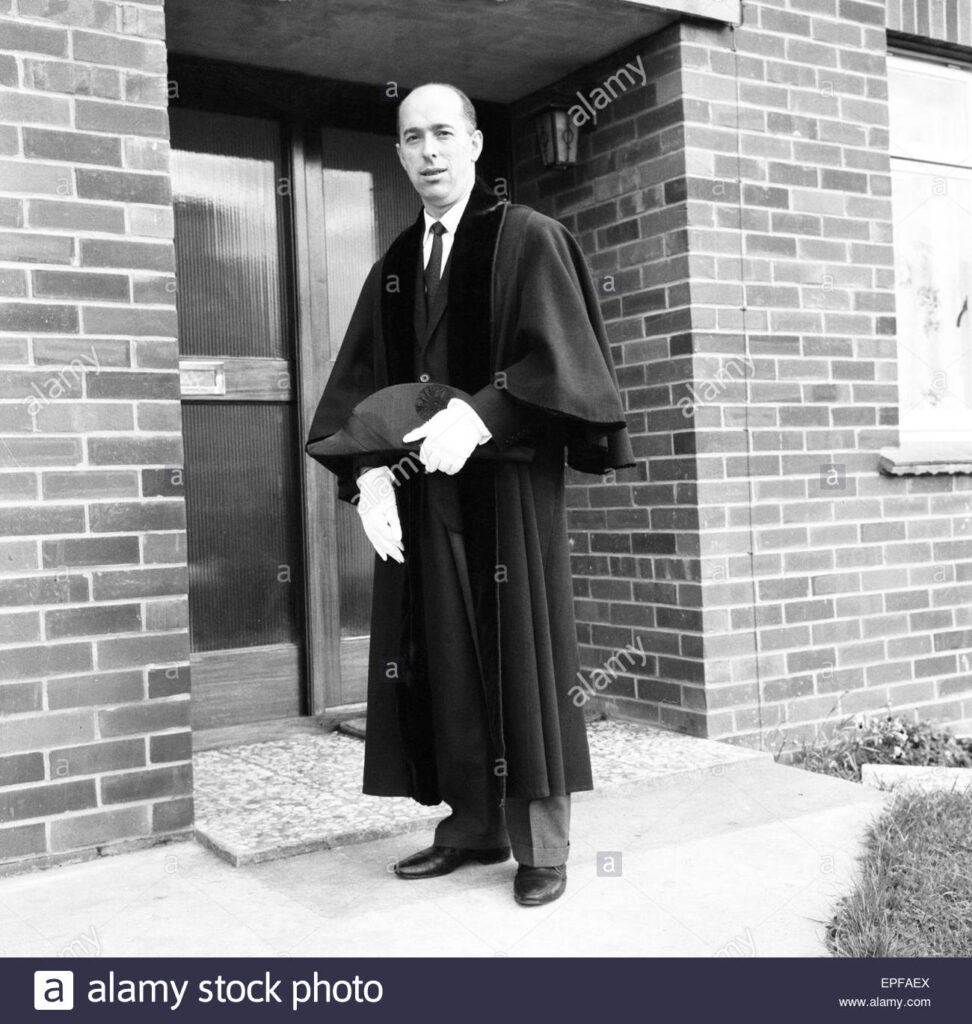

From abject poverty in Glasgow, Paris and rural Italy, to the Royal Army Medical Corps at Aldershot…

.. to a lucky strike with this great woman….

…to a career in civic life, charity and business…

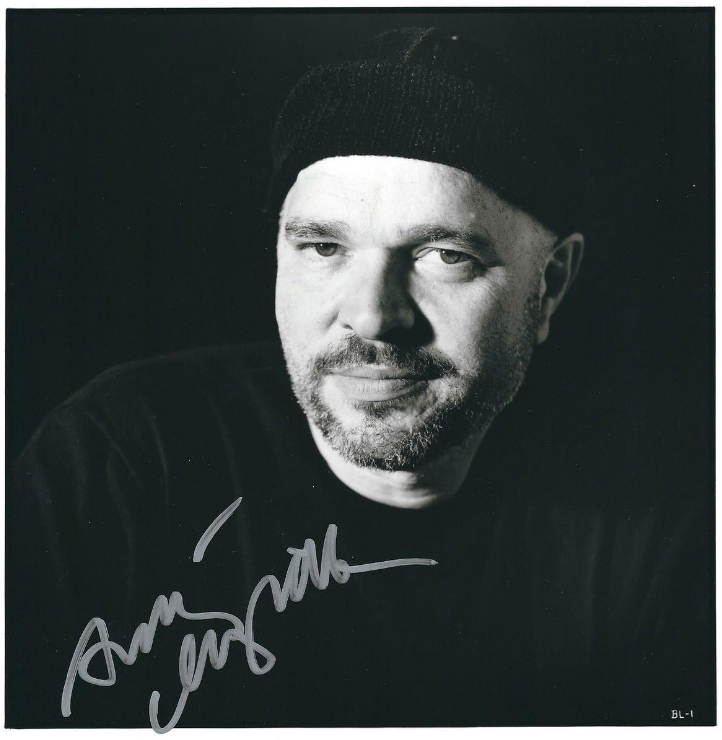

… with a few stop-offs in the movies!

.. and some shattering losses…

… and still going strong, with humour, energy, curiosity, generosity and love.

Bravo, Dad. And thanks for (not) beating me! I got the 99 and the flake!

The Rooftop Sessions

Need a cheer up? Here’s our Louisa “live” from her rooftop in North London.

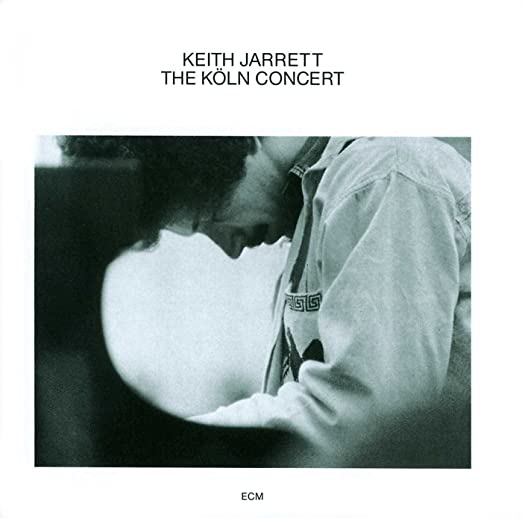

The Köln Concert

Imagine sitting down at the piano and playing the fucking Köln Concert.

Imagine that. Sitting down and giving birth to that thing.

I don’t care how much prep he might have put into it.

To sit down and unload that astonishing, profound, everlasting piece of virtuosity onto an unsuspecting world. It beggars belief.

Its pounding, percussive rhythms, its soaring melodies, its incalculable, seemingly-careless complexities enter into the listener’s very being. For Those Who Know, Köln is a part of them, a part of life.

As solid and defining as the memories of youth. For me it is as vital and essential as the curve of Appley Bay; the aquamarine of the Solent; the wet planks of Ryde Pier; the heady brine of summer; the sound of the SRN-6 hover whining onto its concrete platform; the sight of Mum at the Mayfayre’s Falcon stove; Muriel at the counter; Jean at the baking table; the arid paper-smoke smell of the Commodore’s bins; Vernon the projectionist’s terrifying oxygen bottle; the sound (and the dread) of Dad firing up The Machine; the endless labels and lids; the cream machine; the dusty box of mechanical Happy Wanderer devices which never made it into the ice cream vans; the unsettling Lonely Man Beside A Train Tunnel I thought I saw on the tiles round the bath; riding no-hands with Daz, as we could do, for literally miles; practising our skids on the ice patches of Spencer Road; the anticipation of Ant coming home; my sisters singing So Far Away; the sound of Dad’s keys hitting the sideboard when he got back late from the election count – softer if he’d lost, or with a discernible splash if he was home in triumph.

The Köln Concert sits alongside all of those deeply personal flavours and tastes. But more than that, it facilitates them. It frees the mind and opens it to the heart. It catalyses and romanticises and celebrates. It deepens sadness, it fuels joy, it puts thrust into lust and – most of all – it soars. It convinces you you could fly.

And if you could fly, this would be your soundtrack.

It is that extraordinary.

And a man sat down and made it. Sure, he probably plotted his ideas. Part IIc is so exquisitely well-formed it must have been pre-configured. But the Concert’s opening, a nod to the bells of Köln and that particular audience, seems to have found itself, to have unearthed itself as the pianist patiently, delicately dug into the theme those three bell-notes suggested. It was archaeology with imperfect tools, too – the piano had some problems, but there was no time to replace it, so Jarrett had to make do and play round its issues.

Keith Jarrett sat at a piano on 24th January, 1975, and he made this.

In March, 2020, when I thought my number was up in hospital, this was my number; I played it as loudly as my phone and my nurses would permit. Köln Concert as Covid commiseration.

What am I trying to say? I suppose it’s just awe, plain and pure. Awe at this unsurpassed and mostly-spontaneous expression of genius. And what it tells us about who we are. Who we can be. I write this as a virus terrorises all humanity, America burns with race riots, and politics in the UK, the US, China, Russia and much of Europe have patently failed us. There seem to be few reasons to be cheerful.

But, God, the Köln Concert restores your faith, lifts your soul, replenishes and astounds. When my friend, the artist Gregor Cürten, casually mentioned at a recent dinner that he was there in the audience at that concert, I was nearly sick with envy. In fact, for a few undignified seconds, I hated him, like a spurned husband. Because if I could attend any one creative event, this would be it. Keep your Mozart. And I’ll marvel at Bach as much as the next man. But this one, extraordinary moment – in a career littered with extraordinary moments – is not just piano, and not just music. It is mankind at its most transcendent.